The Table Jesus Would Have Flipped

I. The Line That Won’t Leave Me Alone

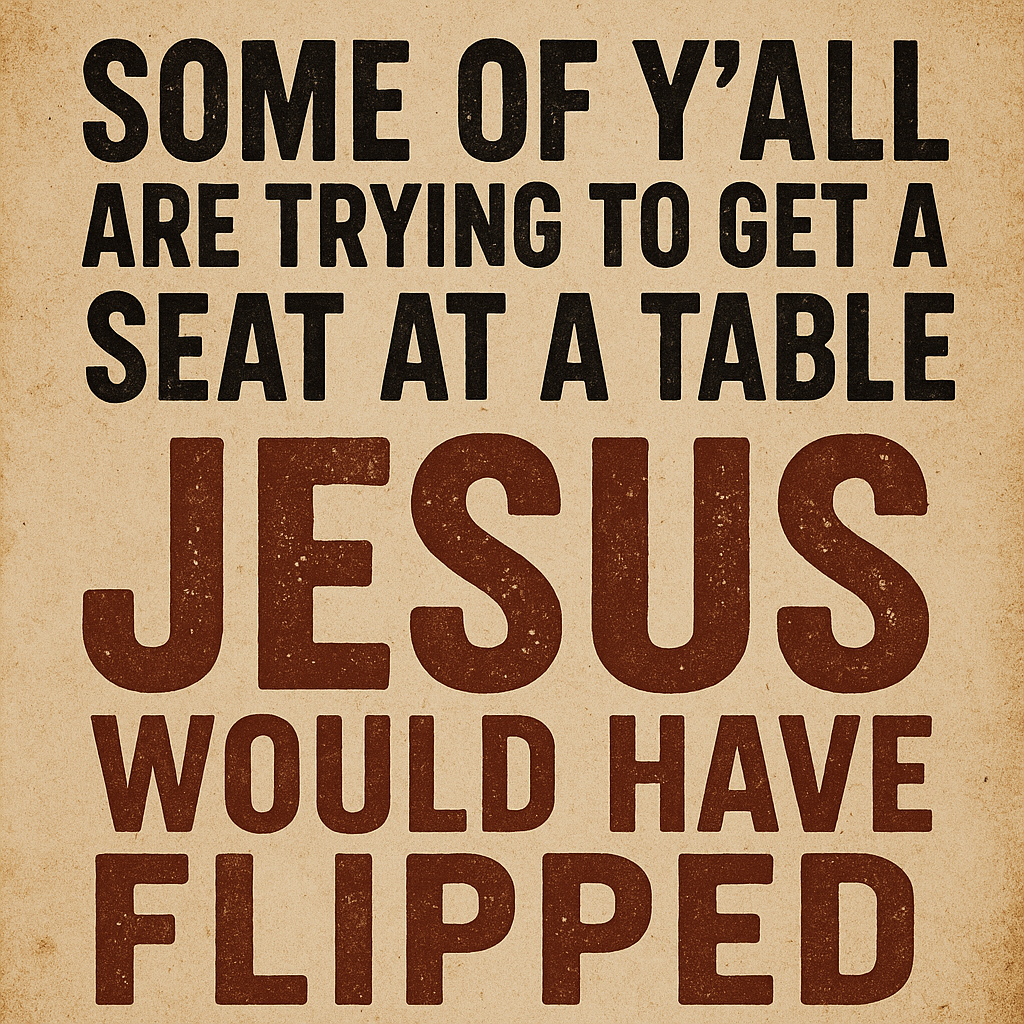

“Some of y’all are trying to get a seat at a table Jesus would’ve flipped.”

I heard it in a TikTok more than once, and it stuck—because the truth behind it is heavier than the delivery. We live in an era where faith is often measured by access: access to influence, to politics, to platforms. The goal isn’t to live like Jesus. The goal, for many, is to be seen with the powerful, to dine with them, to legislate beside them. And in the process, a gospel rooted in mercy and disruption gets repackaged as one of dominance and exclusion.

Too many American Christians aren’t trying to live like Jesus—they’re trying to sit where power sits. And in doing so, they defend policies and people their own savior would have rebuked.

II. Access Over Altruism: The New Gospel of Power

Too many American Christians aren’t trying to live like Jesus—they’re trying to sit where power sits. And in doing so, they defend policies and people their own savior would have rebuked.

Religion has been weaponized for centuries, its ambiguity offering fertile ground for reinterpretation. Its malleable nature allows individuals and institutions to reshape its teachings in the image of their own biases, contextualizing ancient ideologies within the pressures of modern life. In doing so, the core altruism of many faiths becomes distorted, twisted into something that feels righteous not because it is, but because it’s been framed as “God’s will,” “justice,” or “the natural order of things.”

This pursuit of proximity to power isn’t new. From the Roman Empire’s co-opting of Christianity to the rise of the Moral Majority in the 1980s, there’s a long tradition of believers aligning themselves with political might under the banner of moral conviction. But that alliance has always required compromises—compromises that soften the gospel’s radical message and reshape Jesus from a disruptor of unjust systems into a divine mascot for the status quo.

III. Holy Indifference: The Cost of Comfort

On May 30, 2025, Senator Joni Ernst (R‑Iowa) defended sweeping safety net cuts in Ole Yam Tits' proposed budget reconciliation by saying,

“Well, we all are going to die. So, for heaven’s sakes, folks.”

Ernst, who publicly identifies as a Christian, delivered the line with the kind of breezy detachment that’s become characteristic of a new moral posture in American politics—one where fatalism masquerades as realism and cruelty is cloaked in the language of tough love. It’s become culturally acceptable, even fashionable in some circles, to treat the suffering of others as a punchline—especially when those suffering are not considered part of the tribe. The message isn’t just economic; it’s spiritual: They’re not one of us, so their pain is not our concern.

Today, this logic shows up in pastors preaching prosperity while their congregants ration insulin. It shows up when Christian lawmakers vote against food assistance or housing relief, citing “personal responsibility” over communal care. And it shows up in church pews, where exclusion is mistaken for discernment, and cruelty is baptized as conviction. As long as the targets are the poor, the queer, the immigrant, or the unbeliever, the harshness can be recast as holiness.

There’s comfort in this posture. Sitting with power feels safer than standing with the vulnerable. It offers validation, protection, and the illusion of divine favor. But it also demands denial of scripture, of conscience, and of the example Jesus actually set. You can’t carry a cross and a sword at the same time.

IV. Belonging Over Belief: Why People Stay in Broken Systems

I know this pull intimately. I’ve been part of churches that preached love on Sunday and lobbied against compassion by Monday. I’ve watched friends justify bigotry with Bible verses, as though Christ’s main concern was who gets invited to brunch. It’s easy to confuse visibility with virtue, especially when your community rewards conformity more than courage.

To be clear, this isn’t just about manipulation from the top down. Religion is an easy sell—not because people are gullible, but because it offers something deeply human: community, identity, a sense of belonging. In a fractured world, there’s comfort in hearing, “Oh, you go to my church—let me give you a hand.” That’s a powerful pull. It tells people: You’re safe here. You’re one of us. You’re good.

The problem is that institutional religion, especially in its Americanized form, often prioritizes membership over meaning. It becomes tribal. People begin to follow the structure more than the spirit. And once that tribal bond forms, it becomes incredibly easy to conflate personal preferences, political beliefs, or cultural norms with divine will. Christianity, in that context, stops being a call to radical love and starts becoming a mirror for whatever people already want to believe.

It’s not that everyone wakes up and chooses hypocrisy. It’s that the psychology of belonging is stronger than the theology of service, and in too many communities, the loudest voice isn’t the one asking “what would Jesus do?” but “who’s on our side?”

V. Faith as Performance: What Social Media Reveals

Regrettably, I interact with a lot of social media and news. What I see, more often than not, isn’t earnest faith—but a toddler-like rebuke of the spirit of Christianity in favor of dominance, shame, and shallow certainty. Take the issue of queerness, for example. A common pattern emerges:

“The Bible says gays are going to hell!”

“Can you show me where it says that?”

“I don’t have to prove anything to you. You’re one of them. You’re going to hell too.”

“It doesn’t actually say that. Let’s look at the passage you’re referring to.”

“You don’t have a relationship with God. You don’t know what you’re talking about.”

And just like that, the conversation ends—not because scripture was upheld, but because control was lost.

It’s not about truth. It’s about allegiance. The goal isn’t spiritual growth or theological clarity—it’s preserving the illusion that your side is right, righteous, and untouchable. The second that illusion is challenged—even with compassion, facts, or scripture—it collapses into accusation. Because the actual text doesn’t matter. Only the tribe does.

VI. Christ, Country, and the Pickup Truck Jesus

This pattern isn’t limited to sexuality. You see it in immigration debates, conversations about policing, poverty, war—any space where a Christian ethic of love and sacrifice would actually require discomfort or change. Instead of following Christ’s example, the faith has been retrofitted to bless border walls, tax breaks for billionaires, and military dominance. It’s been tailored to fit a specific cultural costume.

There’s a pervasive mythos—deeply American and deeply unbiblical—that casts Jesus not as a poor brown-skinned man from the margins of empire, but as a white, gun-loving nationalist who speaks English, votes Republican, and wants your enemies punished. He drives a pickup truck, too—probably with a flag decal and a fish on the bumper. It’s a Jesus made in the image of American exceptionalism, not the Sermon on the Mount.

People don’t always say it outright, but they act on it:

- Jesus was American.

- Jesus supports closed borders.

- Jesus believes in capitalism.

- Jesus helps those who help themselves.

- Jesus hates the same people I do.

These aren’t theological positions—they’re cultural projections. And the danger isn’t just that they’re wrong. It’s that they allow people to commit harm while feeling holy. They aren’t worshiping Jesus. They’re worshiping an idealized version of themselves, wearing a crown of thorns.

VII. Back to the Table

Maybe the problem isn’t that the table feels exclusive. Maybe it’s that we were never meant to sit at it in the first place. The discomfort some Christians feel in today’s culture isn’t always persecution—sometimes, it’s conviction. A reminder that you can’t follow a man who washed feet and fed strangers while worshiping systems built on exclusion and control.

Jesus didn’t seek influence. He didn’t posture for proximity to Rome. He didn’t ask who deserved help or whether someone had the right paperwork before offering healing. He didn’t cater to power; He confronted it. He flipped tables when the temple—the sacred place—became a marketplace for exploitation, much like Mango Mussolini's Bible and sneaker grift.

And if He, Jesus Christ, walked into many churches or campaign rallies today, I don’t think He’d be looking for a seat. I think He’d be looking for something to overturn.

So if your faith demands silence in the face of cruelty—or asks you to trade compassion for comfort—you might not be at the Lord’s table. You might be at one of Caesar’s. And calling it holy doesn’t make it sacred.